Issue #5: A plastic-fighting hero is born!

Plastic-eating microbes and the enzymes they contain are giving us some intriguing tools for dealing with plastic trash, but no silver bullets

A waxworm, found in recent years to harbour gut bacteria capable of breaking down plastic. Photo by Sam Droege, used under Creative Commons license.

What if there were a superhero who had the ability to control and destroy plastic?

Honestly, not a bad power for modern society or the comic book industry. We’d need a fitting name. Maybe ReWind, for an environmental type. Or PET Hound (you know, like PET plastics). Or Plastik Rapper, a clownish hero with zero musical talent and delusions of fame!

Okay, moving on - what’s their origin story? If Marvel or DC created a plastic-fighting superhero, where would the power come from?

Our hero, Kevin, is a young scientist studying the application of enzymes (proteins that speed chemical reactions) found in plastic-eating bacteria.

Kevin is trying to catch the eye of fellow researcher, Victoria Blaze, a brilliant scientist and former swimsuit model. Devastatingly, he has one of the least glamourous laboratory jobs ever - studying waxworms and the plastic-eating bacteria in their guts.

One night, while working late and role-playing a date with Victoria, he accidentally smashes a container of waxworms. While cleaning up his mess, one of the little grubs bites him, sending super enzymes into his bloodstream (Kevin has very delicate skin). This can only mean one thing; KEVIN IS NOW IMBUED WITH THE POWER TO CONTROL PLASTIC!

Soon, our Worm Guy (a cruel nickname bestowed by a local newspaper) finds himself the target of “The Society” - a shadowy organization funded by plastic producers and beverage companies dedicated to preserving Big Plastic’s power over society, no matter the cost. Can Worm Guy triumph over The Society? Will he ever muster the courage to ask out the radiant Victoria Blaze? Find out in the next issue of WORM GUY!

I may never sign a publishing deal with Marvel on this idea, but plastic-eating enzymes are already a reality.

Before I go further, I want to acknowledge I am late once again with this issue. A loose biweekly publishing schedule hasn’t been working. So I am going to be issuing the newsletter every following Tuesday this month, moving to a biweekly schedule of an issue every first and third Tuesday of the month afterwards.

Back to plastics. The discovery of many fast-acting plastic-dissolving enzymes is wonderful and exciting. Unfortunately, the reality is that these plastic-eating enzymes will need years of study, testing and development before they are ready for commercial applications. And even then they likely will not solve our biggest plastic pollution problems.

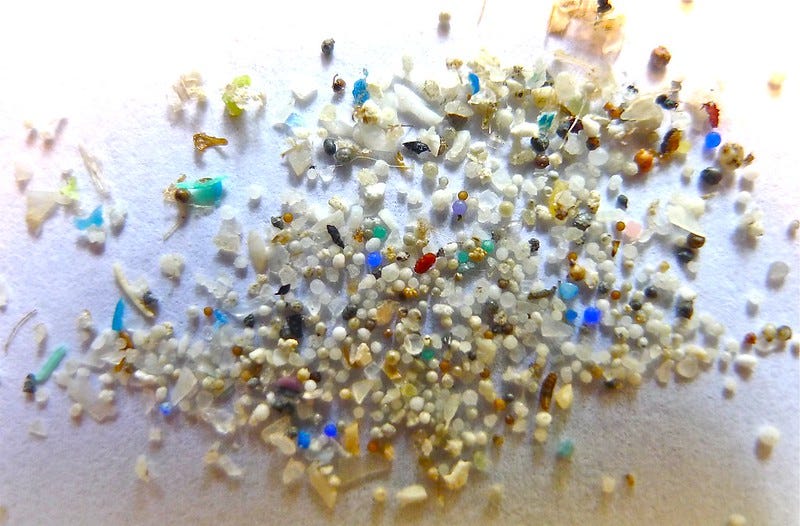

Small pieces of plastic are far more common in the ocean than large chunks (macroplastics). Photo by 5Gyres, courtesy of Oregon State Universit, provided under Creative Commons license.

The most insidious threat from plastic pollution is microplastics - tiny particles and threads of plastic that persist in air, soil, water and the bodies of living creatures. How can mass-produced plastic-eating enzymes be applied in the ocean? There are no giant “islands” of plastic trash in the ocean. Large chunks of plastic are a minority; the majority takes the form of a “thin plastic soup” of particles on the ocean’s surface (with even more sinking to the bottom).

If we did unleash a hyper-effective, rapidly multiplying plastic-eating bacteria into our oceans, how would we prevent them from devouring fishing nets, buoys and essential ocean-going equipment humans are still using?

So, as you’re likely to hear many times in this newsletter, this particular line of study is only part of the solution.

Many of the enzymes being developed are specialized for breaking down PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastic, the kind most commonly used to make plastic bottles and containers.

Other types of plastic can be dangerous to break down. Polyurethane (the kind of plastic a watering can or bucket might be made of) releases toxic chemicals when it degrades. In spring 2020, researchers found a strain of bacteria capable of breaking down polyurethane and surviving the resulting release of toxins. However, research team member Hermann Heipieper was quoted in a Guardian article as saying it might be 10 years before the bacterium could be used at a large scale. In the meantime, we have to focus on reducing production of hard-to-recycle plastic (a de-facto majority of what’s produced today).

Enzymes are promising because they could be incredibly versatile. Trash wouldn’t necessarily have to be sorted to treat for plastics - enzymes could be sprayed on the whole lot.

They’re also energy-efficient, obviously, because they break down plastic in a natural chemical process. The main energy expenditure would be producing the enzymes and applying them to the relevant problem area. Of course, this is all theorizing because these systems haven’t been invented yet!

While we search for the plastic-fighting heroes of the future, take some time to review the articles below.

Long reads:

Hakai Magazine - The haunting nature of plastics: A lyrical meditation on our most insidious creation

In Issue #4, I mentioned “Junk Raft” by Marcus Eriksen as an interesting read that gives you a grounding in the facts and politics of plastics and plastic pollution. Meera Subramanian’s 5,000-word feature in Hakai Magazine is a shorter read that addresses many of the same themes; the omnipresent nature of plastic pollution in the modern world, plastic production and the natural world, plastic pollution myths and more.

Short reads (under 5 minutes):

I’d like to note here that if you’re not already following Marc Fawcett-Atkinson’s reporting on plastics at the National Observer, you should. I’m not aware of anyone else churning out quality, Canada-focused plastics reporting on a regular basis.

New York Times - Here is who is behind the global surge in single-use plastic

National Observer - Online retail - and Amazon - has a plastic problem

National Observer - The plastics you throw away are poisoning the world’s eggs

The Guardian - Call for global treaty to end production of “virgin plastics” by 2040

Thank you all for being part of this newsletter. Questions? Concerns? Plastic trends and news tips you think I should write about? Please don’t hesitate to reach out.